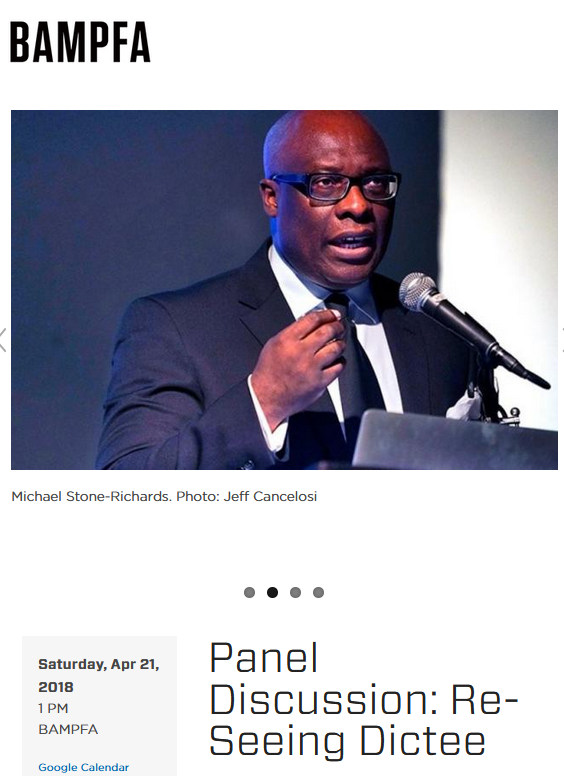

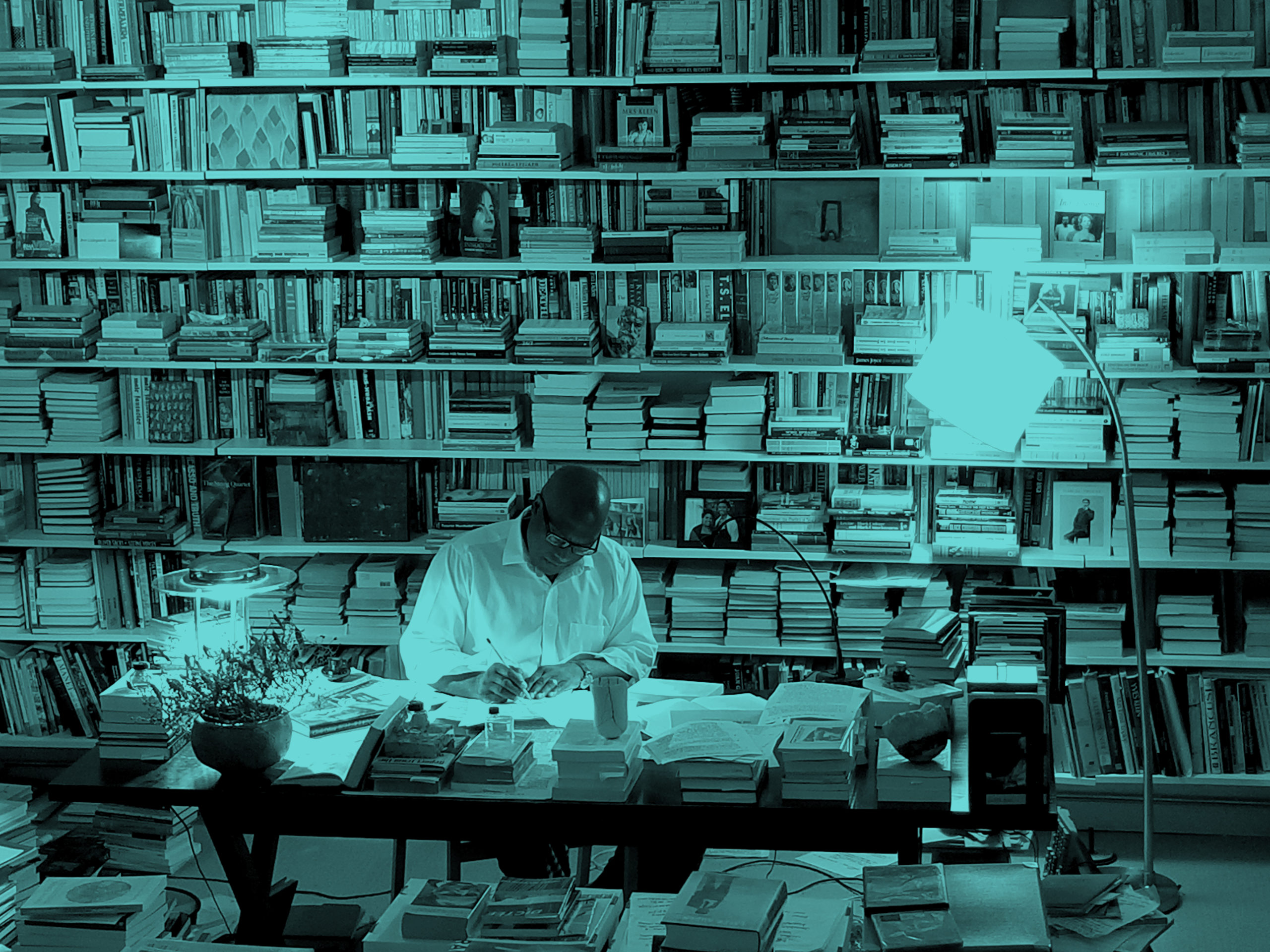

Michael STONE-RICHARDS is a scholar-teacher of critical theory / biopolitics, comparative literary / and visual studies, Social Practice, and the history and theory of modern and contemporary art practice. He has published widely in French and English on the avant-garde in poetry, critical theory, and art. Since his arrival in Detroit, he has become deeply involved in the various parts of its arts and performance community, beginning with MOCAD, where he was a founding member of the Program Committee and a co-curator of the exhibition ReFUSING Fashion on Rei Kawakubo and Comme des garçons; he has also served on the founding board of advisors for the Kresge Arts in Detroit, and is a long-time member of the board of the Friends of Modern and Contemporary Art at the DIA. He has many engagements in the city and organizes the open-format Conversation in the Park which he co-curates with artist Addie Langford as well as collaborations with artists and writers with whom he shares a practice of the Banquet of friends (convivial strategies), and with his students the friendship of collaborative work, thought, and celebration. These engagements with Detroit will continue as part of his appointment as Dean of Programs and Partnerships at Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Michael is the author of Logics of Separation (2011), “Néo-Stoicisme et éthique de la gloire: Le baroquisme chez Guy Debord” (2001), “Failure and Community: Preliminary Questions on the Political in the Culture of Surrealism” ( 2003), and numerous studies on the poetry of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, J.H. Prynne, Paul Celan, and the Negro Spirituals as well as essays in art writing dealing with McArthur Binion, Donald Judd, David Hammons, Arthur Jafa, Theaster Gates, Sonya Boyce, Scott Hocking, Okwui Enwezor, Rei Kawakubo, and fashion and Surrealism. His current research bears on questions concerning the ethics and politics of Care; pedagogy and transmission in the art + design school of the 21st – Century; curatorial practice; Blackness and biopolitics; the French analyst Solange Faladé; and the language of moral perfectionism in the work of Simone Weil, Guy Debord, and John Berger.

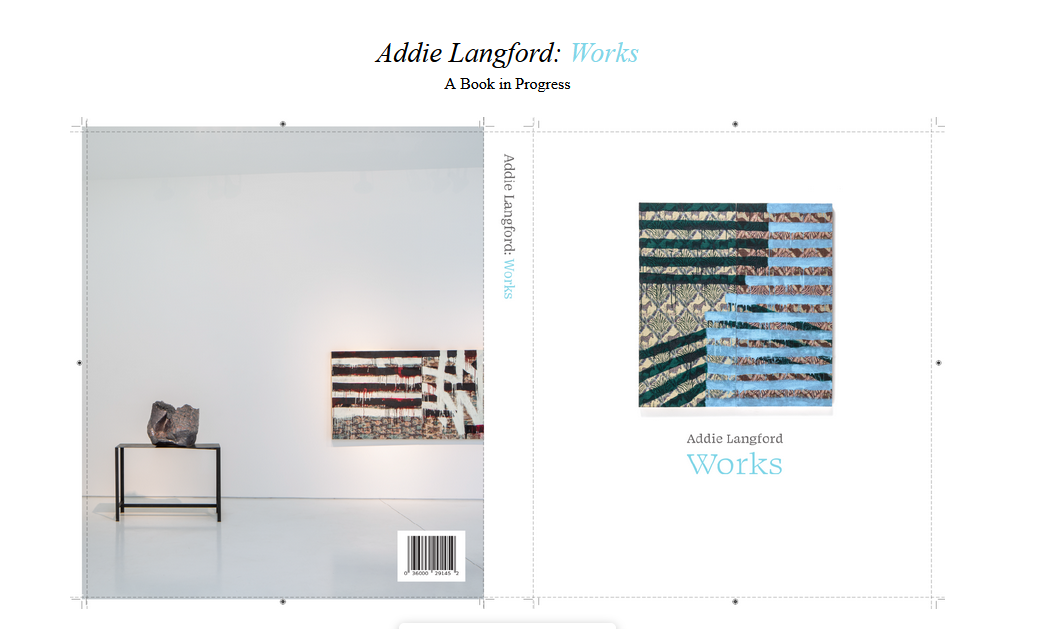

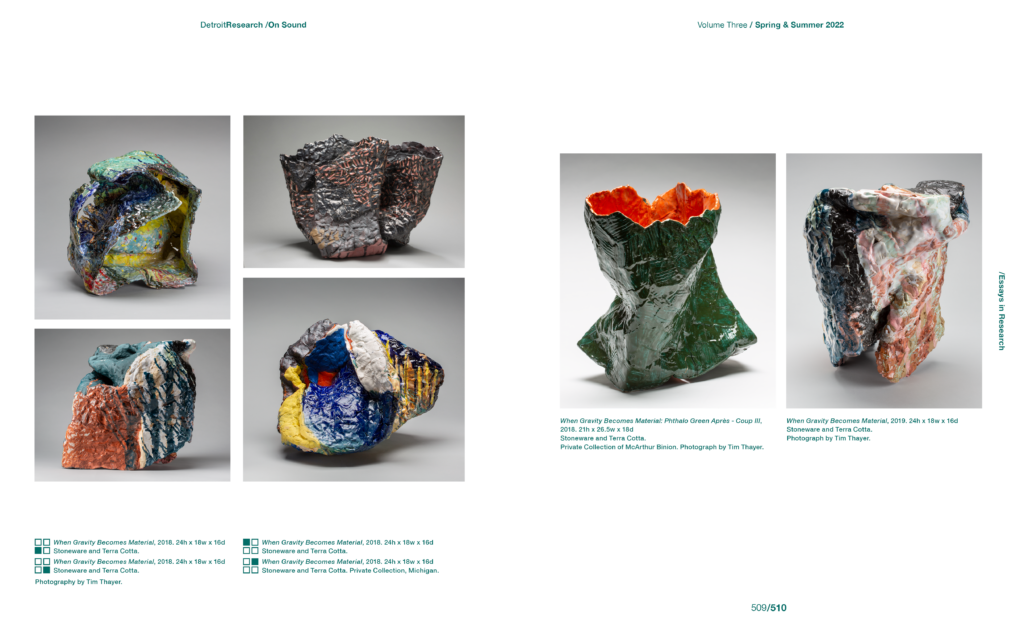

Michael has taught at Northwestern University (Art History and Comparative Literature), then English and Comparative Literature at Stonehill College, Boston, and critical practice and visual studies at CCS in Detroit. His translations from the French - Surrealism, Reverdy, Martine Broda, Blanchot - are an integral part of his conception of critical practice. With the support of a Knight Foundation grant, Michael was the founding editor of Detroit Research, devoted to a broad comprehension of visual and critical studies in choreography, ceramics, performance, post-studio art / Social Practice, and critical theory. With Addie Langford, he recently established Hors Commerce: Detroit Research Collection for the publication and free circulation of new work in critical practice. He also served as Executive Director of the Modern Ancient Brown Foundation (created by McArthur Binion) in Detroit where he set up the Core Program of Visiting Fellows and a post-bac artist residency as well as offering support to artists and institutions across Detroit and beyond (such as Black and Brown Ballet).

Michael is currently Dean of Programs and Partnerships, and Head of the Program in Critical Studies at Cranbrook Academy. Prior to his appointment at Cranbrook, he had been a Visiting Fellow in Critical Studies at Cranbrook Academy of Art, a Fellow at the Centre canadien d’architecture in Montréal, and a Fellow at the Alice Berlin Kaplan Center for the Humanities, Northwestern University. He has received a Graham Foundation Grant for his work on Guy Debord and recently received a Warhol Foundation Grant for his book in progress on Care of the City (forthcoming Sternberg Press / MIT). Living Exposure, from David Hammons to Arthur Jafa: Essays in Art Writing is also forthcoming.

Care of the City is a set of exploratory readings in Critical Practice at the intersection of critical theory with spatial and social practices. What is a city that Care might be part of its nature? The roots of the word Care reveal anxiety, sorrow, attention, lament. Care is both affect and capacity, and one consonant with the political global condition. Everywhere the political condition is marked by retreat, collapse, withdrawal – from treaties, systems, values, social compacts – and no country or region is spared, not even the most privileged of countries or regions which can often be the most hysterical. And just as the globalizing condition, the condition of expansion ironically at one with symbolic contraction, leaves retreat and social collapse in its wake, strangely there is an emerging response of a kind of weak “power” (in the way that gravity is said to be a weak force): the refusal of dominion in favor of Care. In the most fundamental sense, the radical anxiety produced by retreat and collapse of social compacts and values has produced an equally radical awareness not only of mutual interconnectedness with, but dependencies upon, environments, nature, and peoples, that is, entanglements which are often not visible when power works smoothly. Care is the name for the response to this exposure, and the subject across a set of approaches in social / spatial practices / and the poetics of the city. Care of the City is a sustained reflection on this condition of radical exposure through the work of practitioners and poets – Paul Chan with Beckett, Rilke and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, John Akomfrah with Homer’s Odyssey, Theaster Gates with Auden on the need to “rebuild our cities not dream of islands,” Jim Gustafson, Proust, and Paul Valéry in Detroit with Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project and Scott Hocking’s ephemeral structures marking sites of erasure, and Alfredo Jaar and Chantal Akerman with Guy Debord in the rethinking of boundaries / immigration / emergencies.

Curated by the John Cage Trust, Bard College and the Slought Foundation, Performed on the 30th of October Museum of Contemporary Art: Detroit. 2016. Recorded Live.

The great English aesthete Adrian Stokes once said that modern art had accomplished much but that there remains a powerful need for an aesthetics of domesticity. What a remarkable thing to have said! For we do not normally go to art or aesthetics to talk about …domesticity! We go to art, it is said, to be lifted up, to be made to feel the spiritual, to be taken out of oneself, indeed, to forget domesticity. (Is it an accident that in the Detroit art scene there has never been any sustained reflection on domesticity?) Stokes, however, was onto something for one of the great accomplishments of modern art in its avant-garde practices - practices most readily associated with Surrealism, the Situationist International, and Judson Dance – and shared with ordinary language philosophy and critical thought from Wittgenstein to Cavell, from Heidegger to Erving Goffman and the Feminist ethic of Care tradition is the recovery of the everyday as the ground of all human existence. When Heidegger made Care (Sorge) central to Being and Time, central that is, not only to philosophy but to the comprehension of existence, he also made the everyday central to philosophy and existence. When Heidegger said that Care is the response to the radical anxiety experienced when confronted with the collapse of familiarity, he meant the collapse of the everyday, of the ordinary, of all the things that we take for granted – the habits, routines, unexamined practices – that make up our social identities. The collapse of familiarity rips these away from us and leaves us exposed and vulnerable but also as a result able to be-alongside others (strangers as well as environments) without the social masks that we inhabit and through which we project our fears as means of defense of our social roles. At the same time, the collapse of familiarity is the collapse of the domain of the domestic sphere: the home with its rituals and manners of welcome and sheltering; the home and practices of domesticity that we take for granted, whose securities and memories are the background of subjectivity and our ability to face the world – as Rilke wrote “Whoever has no house now, will never have one. / Whoever is alone will stay alone” (“Autumn Day,” trans Stephen Mitchell). In the time of COVID-19 – the desolate time, the destitute time, the meager time, the distressful time – there is much talk of economics (“re-opening the economy” is the phrase) but little to no attention to where the real damage is being enacted: in the sphere of domesticity. What happens when the domestic is no-longer-at-home?

- Michael Stone-Richards

- Unless “we” fall into a state of exception we are all citizens and any and all ethical or political responsibilities befall us qua citizens.

- There is no political or ethical responsibility that the artist or designer qua artist or designer has that the citizen does not first possess qua citizen, and we cannot design citizenship, we can only sustain a fragile culture of citizenship.

- When Beuys wrote that Jeder Mensch ist ein Künstler – We are all artists – this was in part a statement about radical democratic potentiality, akin to Simone Weil: We are all capable of creative action. What pre-empts or interrupts the flowering of such action remains the question of questions that no traditional idea of art or design can comprehend methodologically or epistemologically.

- Participation is existence. Its opposite is alienation. If so, why so much talk of participation? What impedes participation? To speak of participation here is first to draw upon the etymological sense of participation, namely, to have a share or a part in something; but participation is also a movement – intentional, affectively expressive – by which we grasp possibilities and meanings always a part from the locus of movement; above all, participation is world-building practice. Here participation reveals an important feature of our existence, namely, that human existence is always existence or movement in a world beyond bare life, beyond, that is, the Cave. We should more properly speak of an event of participation between partners in the community of being, that is also the City, and as such a phenomenon of shared and complex creation. The restriction of movement is the restriction of existence itself, and this is the basis of being able to say that participation is existence. If though what is also intended is political participation, as must be the case, and all participation is conflict, it should be realized à la Hegel, as Charles Taylor put it succinctly, that “the aspiration to total and complete participation is rigorously impossible,” and would only serve to magnify the conflict inherent in all human activity. Markus Miessen has made much of this Hegelian insight in his meta-thinking on design. What kind of participation and in what kind of community of affect or shared interests are questions that might point to an emerging conception of the artist / designer as thinker / interrogator in need of new institutional expressions.

- It is thus ethically required that any restriction of movement, any pre-emption of shared movement that would impede or restrict the modes of existence of any human existence seeking the community of being, the City, should be challenged.

- But is it as artists or designers, that is, in the name of the artist or the designer that the ethical and then political challenge should be made?

-

First, what the great Harvard, French scholar Paul Bénichou first called the sacralization of the artist / writer, namely, the idea that the artist qua artist had a special calling or vocation, that is, a secularized but still priestly role, is not something that can any longer be taken seriously. Strictly speaking, it was not first and foremost a Romantic idea. It was an idea born of the French Revolution but it expired with Late Romanticism and was critically buried with the various New Art Histories and Cultural Historicisms of the post-1968 generation of critical theorists.

- And what if design, the pre-critical idea of design as solution to problems of efficacious structure, is part-and-parcel of the problem? Is there a competence unique to designers that entitles a generalization to the level of practice as the Marx of the “Theses on Feuerbach” understood practice, that is, as the dynamic totality of embodied social relations? As Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley put it in their recent critical history of design, Are we Human? Notes on an Archeology of Design (Lars Müller, 2016):

The nineteenth-century dream of “total design” has been realized. The famous slogan of the 1907 Deutscher Werkbund “from the sofa to city planning,” updated in 1952 with Ernesto Rogers’s “from the spoon to the city,” now seems far too modest when the patterns of atoms are being carefully arranged and colossal artifacts, like communication nets, encircle the planet. Designers have become role models in the worlds of science, business, politics, innovation, art, and education but paradoxically they have been left behind by their own concept. They remain within the same limited range of design products and do not participate fully in the expanded world of design. Ironically, this frees them up to invent new concepts of design.

Ironically, that is, the expanded world of design would free up designers to leave behind the lazy emphasis upon products, making things, stuff, and designing places for stuff to occupy. Colomina and Wigley quote Lina Bo Bardi as saying that “The grand attempt to make industrial design a motor for renewing society as a whole has failed – an appalling indictment of the perversity of the system.”

- Design in the expanded field, let us call it – why not! – does not have its pedagogy and is emerging without designers or institutional base in design schools. It is not merely 3-D replicators that will soon make definitively redundant traditional ideas of the skill of making, so, too, will the emergence of self-organizing, self-replicating auto-poietic systems. The question of what participation, an event of participation between partners in the community of being, will then mean will have a new urgency.

- Again, to quote Colomina and Wigley:

At the very least such an expanded conception of design as interrogation would not only jettison the concern with stuff, it would expand its thinking into a care beyond the human – our companion species with which we also participate – and become part of a critical activity of biopolitical thought and the non-alienating activity alone worthy of being called participation.

Michael STONE-RICHARDS

This set of theses was delivered as part of the panel “Citizen-Artist – The Role of Participation” convened by Amy Deines at the annual AICAD conference held in 2019 in Chicago.

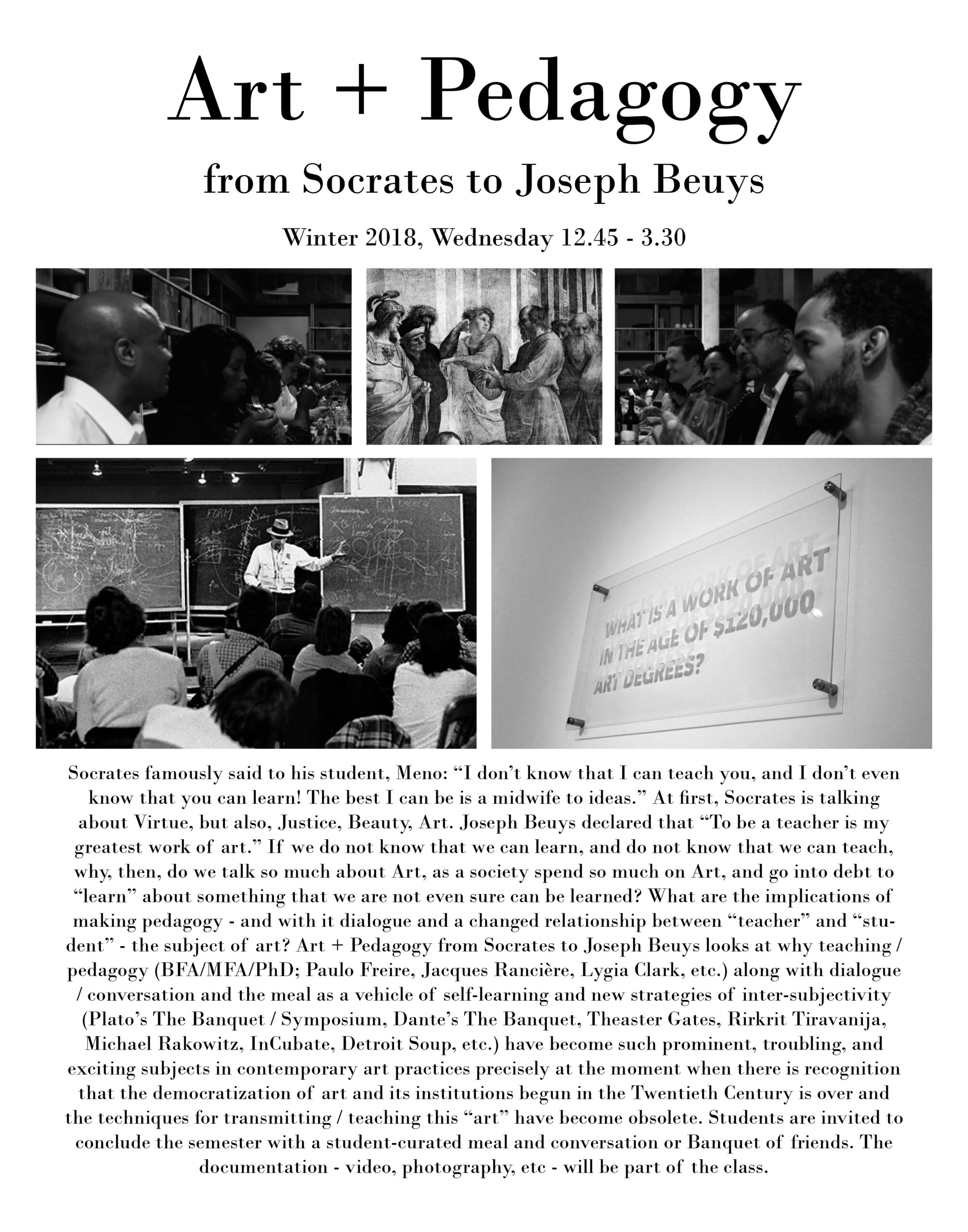

Research / Art + Pedagogy / or, Time in Critical Practice

The passions ignited by discussion of Asher’s post-studio crit – and not a single student had ever heard of Asher, still less his post-studio class – stunned me. I have not infrequently been in a situation when class discussion takes off and as a teacher one becomes an engaged observer trying to stay out of the way, but this went on for three weeks before I said that I would re-work the syllabus and pursue new but related pistes. - For example, Robert Irwin would enter the new iteration of the seminar.

I have a precise memory – and notations – of what was said during these discussions, but let me start here: Students themselves must take some responsibility for the failure of Crits. I was struck by the maturity of this recognition and the quality of the observations which it provoked. Even more, however, the Crit itself was the problem. In Asher’s practice, on the other hand, students saw a whole new practice of temporality and agency: that a Crit might run for 12 or 15 hours did not frighten them but instead excited them; that the “professor” did not speak, or barely so, intrigued them, even more so as they would come to grasp that the implied practice of listening and utmost presence left students to come to their own realizations about the strength and weaknesses of their work;4 from this many students started a discussion about the role of duration in the Crit, being durationally embedded, both instructor and students, hence no outsiders joining the Crit simply to talk about their own taste or aesthetic; above all, what they got a hold of tight was the idea that the silence of the instructor in the practice of the Crit meant that the work was not there to be turned slowly into a copy of their instructor’s work or become an instance of the instructor’s taste. Here Robert Irwin joined Asher – my own deep interest in Irwin was wholly due to one of the most important CCS alums, the artist Michael E. Smith, whose work is in dialogue with Irwin’s thinking on spatiality - especially the Irwin who observed:

Point 1: A main aim of the class was to consider the nature and purpose of teaching / learning as the transmission of values that constitute a field of practice, knowing that, as Plato explored in the Socratic dialogues, values and ideas die and so there is nothing inevitable or necessary about a particular set of ideas that is being currently taught.

Point 2: We read Howard Singerman’s exceptional book, Art Subjects,3 on the history of the MFA in the American academy and how the MFA was explicitly never intended to become, and is not to this day, a degree connected with the ability to teach.

All the time my ideal of teaching has been to argue with people on behalf of the idea that they are responsible for their own activities, that they are really, in a sense, the question, that ultimately they are what it is they have to contribute. The most critical part of that is for them to begin developing the ability to assign their own tasks and make their own criticism in direct relation to their own needs and not in light of some abstract criteria. Because once you learn how to make your own assignments instead of relying on someone else, then you have learned the only thing you really need to get out of school, that is, you’ve learned how to learn. You’ve become your own teacher.5

Observation 1: A key question that emerged from discussions on the Crit, a question which formulated a concept, was the following: What do we want a Crit to be: an artisanal imprinting or a critical practice? Artisanal imprinting pointed to the absorption of the instructor’s studio practice6 the best version of which might be, say, a conservatory approach, whilst the idea of a critical practice, pace Asher, Irwin, but also Roland Barthes’ conception of co-creation and mothering in the space of the seminar, that is, the shared space of learning, pointed to critical practice, research, and knowledge.

Observation 2: There was a fascination with Barthes’ conception of co-creation and mothering as developed in his “To the Seminar”7 – the genre of the German lieder An die Musik (with reference also to Rilke) was discussed as also the transferential dimension in learning – from which the following question: What if the Crit as conventionally established is a refusal of co-creation? This led to an examination of the mothering aspect of Asher’s post-studio crit, that is, the space of the Crit as an envelope jointly created by all who participate.

Cover of Public Knowledge: Selected Writings by Michael Asher, 2019.

The cover shows an installation detail of a work in the Centre Pompidou’s Michael Asher, 1991.

All cultural progress, by means of which the human being advances his education, has the goal of applying this acquired knowledge and skill [that is, practice, MSR] for the world’s use.13 But the most important object in the world to which he can apply them is the human being: because the human being is his own final end. – Therefore to know the human being according to his species as an earthly being endowed with reason especially deserves to be called knowledge of the world [emphasis in original], even though he constitutes only one part of the world.14

Kant goes on to clarify his sense of pragmatic anthropology by saying such knowledge of the world is only called pragmatic “when it contains knowledge of the human being as a citizen of the world.”15 In this respect Kant’s pragmatic knowledge is here a transition between the classical Aristotelian view of practice and the modern view of praxis as formulated by Marx and re-transmitted by Althusser. It is also fundamentally the basis for any critical account of practice as central to the modes of contemporary art as critical engagement with world-making and demystification of representations, that is, the ideologies masked as realities which serve to distort the relations to the world. Eventually this mode of thinking about practice and pedagogy in the art and design school would become formulated using the established language of the PhD, namely, that document of research that makes a contribution to knowledge, or, in the language of Critical Practice, the production of knowledge since there must always be awareness of the material conditions of knowledge-production. (It is, of course, by no means clear that Asher would have been invested in the idea of the PhD in Art, and certainly not as a qualifying degree for teaching.

Life consists in learning to live one’s own, spontaneous, freewheeling: to do this one must recognize what is one’s own – be familiar and at home with oneself. This means basically learning who one is, and learning what one has to offer the contemporary world, and then learning how to make that offering valid.

The purpose of education is to show a person how to define himself authentically and spontaneously in relation to his world – not to impose a prefabricated definition of the world.20

Endnotes

[1] On Detroit Soup, see Amy Kaherl’s “Dinner Music,” her memoir in progress, in this issue of Detroit Research and her reading online at Detroit Research website.

[2] Cf. Sarah Thornton, “The Crit,” Seven Days in the Art World (New York: Norton, 2009), 41-74.

[3] Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

[4] I continue to see in this practice of listening and agency for the students a version of what the Lacanians of the École freudienne de Paris, between 1967 – 1969, called la Passe (the pass), which was an experiment in the very foundations of institutionality by allowing candidates for the status of analysts to declare themselves when ready to assume the role of analysts. It was a dangerous but still important idea especially worthy of further investigations precisely in a culture of the artworld where no one believes that the acquisition of a degree eo ipso confers the status of artist – thus a denial of the performative act of conferring a degree - thereby bringing into question what kind of education (or training?) it is that one has received as well as to foreground, going forward, what education for art and design might become as economic and demographic pressures mount on all aspects of post-secondary education. And yet the art degree – what a practitioner like Rick Lowe, in the context of Social Practice degrees, refers to somewhat contemptuously as credentials – retains a gatekeeper function to the Artworld. That there is a pedagogical dimension to Asher’s practice is evident - institutional critique is nothing if not pedagogical - the question, rather, is how to read the pedagogical dimension, and its (latent?) Lacanian registers. Here the presence of Lacan in the Centre Pompidou’s Michael Asher (1991) could be a starting place. In the Art + Pedagogy seminar we have explored this dimension of Asher’s practice through an ethics of temporality as this bears on but without being limited to the Crit.

[5] Robert Irwin, quoted in Lawrence Weschler, “Teaching,” Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert Irwin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 120.

[6] As one student commented to the class: “There was a moment when I realized that all that I was being taught was my teacher’s studio practice!”

[7] Cf. Roland Barthes, “To the Seminar,” The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 332-342. The BAK art school in Utrecht organized an artist symposium on the critical practice derivable from Barthes’ “To the Seminar.” See the discussion moderated by Vivian Sky Rehberg in 2017 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNKzPgP8gkU.

[8] Cf. Herbert Marcuse and Bryan Magee, “Marcuse and the Frankfurt School: Dialogue with Herbert Marcuse,” in Bryan Magee, Men of Ideas: Some Creators of Contemporary Philosophy (London: BBC Books, 1978), 61-73; on Critical Theory as negation of philosophy (in parallel with Heidegger’s negation of metaphysics, and the avant-garde negation of art and poetry and music), cf. Herbert Marcuse, “The Negation of Philosophy,” Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (1941) (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1955), 258-262. It would be relatively easy to show that Critical Studies as developed in the contemporary and international art + design school is the discursive disciplinary / pedagogical equivalent of Critical Theory, that is, Critical Studies is the negation of liberal arts in favor of a new critical practice developed from the intersection of Critical Theory and art + design understood as discursive formations. Within university culture - where “humanism” can indeed have richly innovative defenders - “liberal arts” is an all but meaningless term as disciplinary transformations have all but made liberal arts as a foundation of knowledge redundant. Certain important institutions such as Stanford, Chicago, Columbia, or St. John’s College which have a commitment to (an expanded conception of) a Great Books approach cannot be understood as teaching liberal arts in the ordinary sense, rather they have become a training ground in a certain mode of perception through reading (whether the text being read is mathematical, astronomical, or literary).

[9] On the question of the PhD / terminal degrees in the Arts, see the very illuminating NASAD Policy Analysis Paper, “Thinking about Terminal Professional Degrees in Art and Design,” October 1, 2004. Available at https://nasad.arts-accredit.org/publications/assessment-policy/nasad-policy-analysis-papers/. Accessed 05 – 23 – 21.

This document makes clear the extent of tension within the Art + Design school over the issue of the PhD in the Arts as a new terminal requirement; equally clear is NASAD’s refusal to take an official side in the debate.

[10] And the Conservatory is the highest form of this practice – the Conservatory in music, in acting, etc. Might it be possible to think of Black Mountain College, in its time, as an experimental Conservatory? Where, that is, the conservatory is a stricter community of interests and passions, more singular in its orientation, with no obligation to an abstract “general education”?

[11] Michael Asher, “Notes on professional degrees in studio art” (ca. 1988), in Public Knowledge: Selected Writings by Michael Asher, ed. Kirsi Peltomäki (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2019), 203.

[12] Stephan Pascher, speaking with Michael Asher, “Conversation with Stephan Pascher on Teaching” (2005), in Public Knowledge, 235.

[13] For the world’s use, that is, practice – if it is not simply the production of stuff – must be reflexive. The production of things, to be clear, is also one sense of Aristotelian poiesis.

[14] Immanuel Kant, “Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View,” in Anthropology, History, and Education, ed. Günther Zöller and Robert B. Louden (Cambridge: CUP, 2014), 31.

[15] Kant, “Anthropology,” 231-232. Emphasis in original.

[16] It does not hurt because some person in authority wants to abuse their authority, impose their prefabricated knowledge on a young mind in the name of a personal conviction, which amounts to little more than a form of abusive implantation. The Socratic example shows that learning must also hurt for the person who would presume to call themselves teacher, not least, as Kierkegaard explored in his readings of the Meno, because the teacher may not be able to teach – think Moses in Schönberg’s Moses und Aron (1932 / 1957) – or because what there may be to teach may not be transmissible – think, say, Hölderlin’s Empedocles or Paul Celan’s “Pallaksch. Pallaksch,” for which cf. Paul Celan, “Tübingen, Jänner,” Die Niemandsrose / NoOnesRose, in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry, trans. Pierre Joris (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2020), 264-266; and cf. Søren Kierkegaard, “Thought-Project,” Philosophical Fragments, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), and Kierkegaard, “The God as Teacher and Savior,” Philosophical Fragments, 23-36; and finally, Jacques Lacan’s Séminaire II on “Questions à celui qui enseigne,” Le moi dans la théorie de Freud et dans la technique de la psychanalyse (Paris: Seuil, 1978), 241-257.

[17] Samuel Beckett, Proust (New York: Grove Press, 1981), 21.

[18] Cf. “Aporias of Attention,” forthcoming in Michael Stone-Richards, Care of the City (Berlin: Sternberg Press).

[19] Paul Celan: “ ‘Attention’, if you allow me a quote from Malebranche via Walter Benjamin’s essay on Kafka, ‘attention is the natural prayer of the soul’.” Paul Celan, “The Meridian,” Collected Prose, trans. Rosemarie Waldrop (Manchester: PN Review / Carcanet, 1986), 50; and Simone Weil: “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.” Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace (1947), trans. Emma Crawford and Mario von de Ruhr (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 117. Faith is a translation of the Greek pistis, also trust. Learning presupposes trust, but the classroom is also an arena of love, and this is what all reflections on transmission / transference come to realize.

[20] Robert Merton, “Learning to Live,” Love and Living, ed. Brother Patrick Hart (New York: Harcourt, 1979), 3.

[21] My own thinking on the question of transmission has long been shaped by Wladimir Granoff, Filiations: L’avenir du complexe d’Oedipe (Paris: Minuit, 1975), but also Solange Faladé’s final seminar for the École Freudienne before her death on La Transmission (2001 – 2002).

[22] Cf. the “Conversation” between Michael Craig-Martin and John Baldessari in Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century), ed. Steven Henry Madoff (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2019), 41-51.

[23] Louis Althusser, “Qu’est-ce que la pratique?” Initiation à la philosophie pour les non-philosophes (Paris : PUF, 2014), 163. Emphasis in original.

[24] Cf. Susan Jahoda and Caroline Woolard, Making and Being: Embodiment, Collaboration, and Circulation in the Visual Arts (New York: Pioneer Works Press, 2020).

[25] Cf. Molly Beauregard, Tuning the Student Mind: A Journey in Consciousness-Centered Education (Albany: SUNY, 2020).

[26] Cf. David Kirp, “Community Colleges should be more than just Free,” The New York Times, May 25, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/25/opinion/biden-free-community-college.html?campaign_id=39&emc=edit_ty_20210525&instance_id=31506&nl=opinion-today®i_id=66849993&segment_id=58953&te=1&user_id=4ee170ec26ea24442e7b658c8dd82fae. Accessed 06-07-21.

Religion and Economy of Affect: A Reading of Love is the Message, the Message is Death

Undernneathness—

Surface—

Work in McArthur Binion

Object—

Attention—

Environment

Retreating/Retracing Space: Scott Hocking’s Diagrams of Visibility

Work is a foretaste - a preliminary

experience - of death.

William Stringfellow, Instead of Death

King Henry VI, Part 2, IV.ii.19-201

The Hand in the painting of McArthur Binion. First, the seductive surface. On approaching the painting of McArthur Binion – whether for the first or the umpteenth time – it is the surface that attracts, that seduces: the textures are soft and rich, delicate in the way that surfaces laid down by slowly made crayon or ink can be, the patient gridded lines clearly hand drawn, the face of the artist bent over closely to the plane, almost breathing on the soft crumbly surface of crayon and ink, the pressure of the hand, the fingers intent/tion – first intention, as it were – not only making but being captured simultaneously, not only depicting but being in the latency of the frame. There are moments, as in the DNA series exhibited in Chicago in 2014, when the surfaces of Binion paintings are like jewels of glistening light and as a viewer one simply wants to hold back a little and not hasten the reveal, not allow any perceptual moment to become too quickly resolved into an image – any image - but simply to allow the play of surface textures made by the varied force and lightness of this touch, this hand, of this artist. Rarely is it such a pleasure not to know, and simply to allow oneself, one’s looking, one’s seeing to be trained by the surface, led by the hand, through the touch of the work. At a certain distance, however, a sense of relief – physical relief – begins to allow itself to be glimpsed, and with it another kind of work, a kind of sculptural work of relief as forms – vaguely – allow hints of their underlying presence through the texture. At first, what seem to be other marks and markings, under-markings, are slowly revealed as letters, in rhythms of letterings, glimpses of words and wordings in groups revealing names / dates / locations sometimes in whole, often in parts. The medium reveals more than one support. Paper, maybe. Names. Numbers. Addresses. Yes. Dates. Or a map. Of Mississippi. Or photographs, fragments of photographs. Portraits / unknown? Anonymous? Self-portraits. Lynching. And all at once the perceptual plane dissolves, re-adjusts itself between the seductive and the repulsive, as if one part of the painting recoils from another in the same temporality as one part of the mind of the viewer also recoils in shock from its own recognition. At first, you, as viewer, think there is something buried – stories, histories – but the painting is a seduction in which the handling of memory is a masking of the blow without which masking there would be no distance to allow the viewer the time of recognition, of acknowledgment. The acknowledgment of work. The memories that are handled as phylogenetic memories, memories, that is, that an individual carries for a group, a species, a people: the child in a large family – in Mississippi – of cotton-pickers. The life of labor for an entire family and people. The geographic displacement of the family along with thousands, eventually millions of others from Mississippi and The South northward in search of work and a different state of mind – 12 Million Voices, says Richard Wright, seeking work and “to escape these marked-off areas of life.” Art is, though, a marked-off area of life for the young Binion, a zone of engagement that allows for needed autonomy from the family, as well as offering a means to reflect upon the labor of the family and the nature of labor to which the family – the species – is condemned, or, too, labor as means of escape, liberation. Suddenly the many beautiful, troubling textures of Binion’s oeuvre seem to assume a figuration – the hand – and a subject: what the hand, the instrument of instruments, as Aristotle put it, does, namely, work in the construction of a world. I think of the recent works – for example, the paintings in dialogue with Saarinen in the recent Binion / Saarinen: A McArthur Binion Project at the Cranbrook Art Museum – of which Route One: Box Two, 2017 [oil paint stick and paper on board] has become something of a talisman for me for the way in which the minimalist grey surface of grids yields to grids nested within smaller grids – from the frame to the clear sense of the division of the picture in two halves, then into larger boxes, each diminishing into a smaller scaled version of itself nested within to reveal the movement of language as a form of light within the smallest hand-drawn and so not quite rigid grid, almost as though the grids, that is, the unit of measurement, are made up of bodies (metonymically: the middle passage?) not abstract (modernist) forms, bodies delivered by hands… The Standard Certificate of Live Birth [in Mississippi] can be read in several of these works including Lehmann Maupin’s Route One: Box Two. The standard is the abstract norm, but the part refers to what has been delivered by hand, namely, the result of labor, the living body of the child. The hand, in Binion’s work, is a stand-in, a metonym, for labor, fragility, death.

For Jane Schulak + Culture Lab Detroit

It is present with equal insistence and knowing literalism in Theaster Gates’ Tar Painting series, 2012, inspired, he says, by the labor of his father as a roofer; and think, too, of Gates’s 2012 White Cube exhibition My Labor is my Protest where, in conversation with Tim Marlowe,2 Gates speaks of exploring through his practice “a conversation about labor [and] the role of performance and the possibility of beauty”; where, in the same interview, he also says that “my dad was a roofer for much of my life, and I think that I’ve come to my creative hands as a result of learning to build buildings and roof with him.”3 Finally, Gates explicitly situates his father’s labor as a form of sacrifice which frees him, Theaster Gates, from the need to be angry: “and part of the reason that I have the luxury of not being angry is because my dad labored so hard - so there is a consciousness of the history of struggle.” (Theaster Gates in conversation with Tim Marlowe, White Cube website, 2012). Most telling in the White Cube conversation, however, is Gates’ (acknowledgment of) mourning the death of his mother in 2010 of whom he says that she helped make his work possible even as she did not understand it but, even more pointedly, that he did not seek to bring her into his work, which is also to say, his world, and he did not wish to repeat this omission with his father. In another context I shall delve further into the language of mourning - the public act - shared by Gates in this conversation. Here, I simply wish to foreground the connection Gates establishes amongst labor (both his father as a roofer working with tar and his mother in some sense subsidizing the beginning of his art), mourning (his mother, but also proleptically his father of whom Gates says that he did not, after the death of his mother, want to repeat the same mistake with his father), and Art (here represented by “Jasper Johns,” in a tellingly odd passage the sense of which requires that it be treated as a parenthesis and the sentence incomplete). I quote in extenso as it is in many ways a remarkable passage:

My mom died in 2010, and I think that I really hated myself for not having her

understand better what I was up to on the day-to-day; and especially because she

financed so many of my crazy ideas … I just never gave her the nod, the respect,

to trust that she would understand this crazy world that we occupy, and I just didn’t

want that to happen with my dad. (In a way, we could say that the Tar works are a kind

of response to … um … Jasper Johns … that there’s a … that from reading about Johns,

there was a kind of insistence upon only considering the work at even, you know, as

people move on, they say, “No, Johns, that was about your dad, man! It’s about,

you gay, dude! You gotta deal with that! You gotta deal with that!” “I’m not gay! This is

not about my father!”) And, so, I think that in a way, my dad’s 78, my dad’s gonna pass

[...] my dad is aging, and it just seemed, it was only this moment that I realize that my

first Gift was roofing, and that my dad was actually the beginning of my artistic practice,

because I had to labor with him, and I had to help him take care of his buildings as a very

young person - and I never thought about that as fodder,4 potential fodder, until I was in

the middle of my show here, and I realized that in these moments, when my dad is aging

and things are decaying - spring is turning into winter in his life5 - that I didn’t want to

miss the opportunities [...] from having direct engagement with the people I love … and I

felt that my dad had loaded content that was super good and he was a helluva of a

fabricator who could roll with me through a successful body of work!

Quick - as there will be other occasions to unpack in detail this remarkable passage: In this passage Gates discusses the following implicit relations:

“Art” is Jasper Johns - Labor is the Father - Mourning is the Mother.

Consistently labor is the physicality of what is undertaken by the working-class father (tar, roofing), whilst Johns produces work, and Gates says that his father can roll with him, Gates, “through a successful body of work.” Again, moving quickly, Gates wants to say that Johns represents a conception of Art that insists on the work itself, by which one presumes he means a certain kind of autonomy of the work of art and the mental processes that it entails or entrains; Gates, on the other hand, at least in this moment of acknowledgment in “direct engagement with the people I love,” wants labor, contra Johns, to represent - or better, even, indicate, point to - a beyond of Art, an outside of Art, beyond the white cube (“there are things that are more important to me than White Cube gallery,” he will say): labor is one such, but so, too, is mourning. This outside of Art can lead to a revalorization of Blackness in Art as well as Blackness and Abstraction. The association of Blackness with labor marginalizes it in terms of modern art (and such is also the case for working class art per se in the economy of modern art6), but the implicit relation with mourning, Black mourning, might change the way of thinking about the materiality and language of abstraction - not Malevich, not Mondrian - to allow a conception of abstraction based upon neither a semiotic of disembodiment (say, primitively: Aurier; say, in its most powerful technology: Mallarmé, but in all cases post-symboliste) nor the historicity of art language (say, Binion and Whitten speaking always about not being of art history),7 but rather a conception of abstraction as veiling (of grief) or masking (of power) anchored in different material practices, whence labor.8 The Tar paintings declare in all their surface viscosity the class-based labor of the father: there is nothing to see beyond it (there is no transcendence à la Mondrian, à la Malevich, or Kandinsky): this black substance is the substance of labor itself. It is pure function. It fits where it must. The Tar works also and simultaneously block vision - there is nothing to see into - and so they veil, protect the grief of loss (the personal), thereby making for (public) mourning.

More than ever I regret that I was not able to be present at this exhibition at the White Cube gallery in London! It is only after listening to this remarkable passage and requesting permission to reproduce an image of Gates producing Tar work with his father - an image which I first encountered online - and was politely informed that “This is not a work that we allow to be reproduced” that I began to think more clearly as to why it might be that the photography of Gates and his father with Tar work production as reproduced in the exhibition catalogue, My labor is my protest, are all reproduced in varying degrees of low-res quality.9 (A new kind of low-res, different to what appeared in the 1980s in mail art, is now current in advanced practice: in Paul Chan’s Waiting for Godot in New Orleans: A Field Guide (2007), in Arthur Jafa’s akingdoncomethas (2018), and in each case there is a distinct significance of mourning. - And may be this practice of the low-res as marker of mourning and limited un-masking might be seen, too, at work in Okwui Enwezor’s Catalogue for Documenta 11, Platform 5: Exhibition the first 30 (unpaginated) pages of which, compiled by Nadja Rottner, consist of montages of (relatively) low-res documentary photographs of various catastrophes of our modernity - AIDS, (civil) war, state terrorism, guerrilla terrorism, forced migration, genocide, scenes of sweat labor in the manufacture of consumer commodities - as if the lowered quality of resolution (but which of the available senses of resolution?) suggests a diminution, a lessening in some way (the mystery or the alchemy of the commodity?) the result of circulation within the neo-liberal economy of commodification.10 - The refusal of high definition (and the attendant refusal of circulation) might well be grasped as an attempt to guard, to secure, to retain something from dissipation and even prurience. It would be to keep from full view, and here in Gates, to convey the sense of the image as somehow incomplete and so not fully commodified.

(Susan Cross and Larry Ossei-Mensah, Pitch, MASS MoCA, 2018. Text available online at MASS MoCA website.)

There is of course more, much more, that can be said about this important work of an emerging artist, not least on the role of the “MOTHE/R […] HER” and related questions of natality... We could return to Gates’ Tar works and see in them, too, a deep concern with natality and the way in which natality foregrounds the need to change stories or narrative commencements. Suffice to say that a new visual language is being configured out of and around questions of world, world-making, subjection, and physical labor precisely when the digitization of representation (and lived experience?) has become irreversible - and maybe it is surprising just how varied is this visual language as it articulates a new subject in art.

And snow, scarce as any Northern cotton, or, David Hammons doesn’t work hard like James Brown

For Max Dax - Berlin / Detroit

W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Black Worker,” Black Reconstruction in America, 1860 - 1880

Finally, but by no means exclusively, this insistence on Black labor is present, too, in David Hammons’ Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983, Cooper Square, New York, near the Cooper Union Art School, where David Hammons laid out rows of snowballs for sale in New York City, for what is Bliz-aard Ball Sale if not the negative of Negro Work? Here is Hammons as recorded in an oral history: “I’m not working that hard. When you find a found object, the work is halfway complete.” (David Hammons quoted in Elena Filipovic, “The Color of Money,” David Hammons: Bliz-aard Ball Sale (London: Afterall Books, 2017), 79.) And: “I’m not going to put that much energy into an art object to prove to these folks that I’m legitimate. […] But now that I’m not going to spend like, uh, the rest of my life overworking, like James Brown, the hardest working man, he up sweatin’ and screamin’ and crawlin’ on the floor to prove to these folks that you’re a good singer. I’m not gonna do this shit.” (David Hammons, ibid, 79-80.) The art historian Elena Filipovic comments, “After all, what could be more simple and less work[-like] than making snowballs in winter?” (Elena Filipovic, ibid, 80.) This witty nonchalance is the reductio ad absurdum that makes the point of the labor of the black avant-garde, for as Hammons knowingly comments, “Ain’t no black person gonna pay you for a snowball. [laughs] That’s not gonna happen.” (Hammons, ibid, 89.) And Hammons has in mind not only “no black person gonna pay for a snowball,” he has in mind, or rather, the work brings into its orbit - its metonymic web - Black artists who are focused on the kind of work that would find - or is it, fit? - its market conditions, surrounded as Hammons was - especially in New York - by a commercial culture of painting where “Other Black artists [in New York] couldn’t understand why you would do it [produce something] if you couldn’t sell it.”11 When Hammons, here in his interview with Kellie Jones, speaks of other Black artists, he has in mind other Black artists unlike Senga Nengudi who, in Los Angeles, was conceptual when he, Hammons, “was [still] working in frames,” but who, through sharing a studio with him, helped him become more conceptual just as she in response to his presence became more figurative, “That’s when she started doing the pantyhose [i.e., not your communal garden figuration, MSR]; those pieces were all anatomy,” and this following on from “when she used to put colored water in plastic bags and sit them on pedestals.” No one would speak to her and “She couldn’t relate.” Nengudi made the move to New York “and still no one would deal with her because she wasn’t doing ‘Black Art.’ She was living in Harlem. So she had to leave here and go back to L.A. and regroup.”12 There is more than a little anger (mixed with astonishment? at the blindness? at the self-defeating lack of self-awareness?) in Hammons’ tone as, crucially, he points to a different economy: “Then I came in after her; I said: ‘I’ll try it, I’ll try it with my shit,”13 which is not only the language of refusal (James Brown has his shit, afterall) but a marking of transition to the magical substance of shit that Hammons can deploy as he channels, plays with the bad areas. Here is Hammons again: “There were no bad guys here [in New York], so I said ‘Let me be a bad guy,’ or attempt to be a bad guy, or play with the bad areas and see what happens.”14 Nengudi and (her refusal of) the submission of “Black Art” to the market were material and psychic conditions for the emergence of Hammons’ limning of a possible economy of anti-commodification where he played with bad areas where “nothing in it was for sale,” coming up “with an abstract art that wasn’t salable”:

These things were brown paper bags with hair, barbeque bones, and grease

thrown on them. But nothing was for sale. [My emphasis] Other Black artists

here couldn’t understand why you would do it if you couldn’t sell it.

And:

I came here with my art in a tube. I had a whole exhibition in two tubes. I laid

that on the people here and they couldn’t handle it, nothing in it was for sale.15

David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983, Performance documentation.

Courtesy: Tilton Gallery, New York.

Hammons speaks of the contact with Nengudi (“So by us sharing a studio”) as precipitating a new mode of practice which in being outside commodification resulted in forms or, better, following the late Pierre Fédida, informal substances from playing with bad areas, psychic bad areas and bad cultural areas: brown paper bags (bad enough) but with hair (Jews and Blacks have a thing or two about hair), and barbeque bones, and grease.16 At their moment of origination these informal substances are outside the art frame and this feature or aspect alone allows one to grasp them as part of a collapse of the work (oeuvre) in a movement toward the event (evénément), and indeed, in both Nengudi and Hammons performance - with a pronounced cultural-therapeutic dimension which draws upon identifications in series and which also falls outside the art critical model of discrete form - will assume increasing importance. (Here, it becomes unavoidable, for me at any rate, not to see that Hammons’ description of Nengudi’s practice evokes the parallel practice of Lygia Clark and Clark’s movement from discrete abstract objects to performative object-situations with therapeutic goals.17)

In light of the contact - and there can be no contact that does not leave a trace - and the encounter with Nengudi and the resultant playing with bad areas that makes available or possible the range of informal substances not for sale as outlined above, it remains that not only selves but objects, too, need testing, and the test (épreuve) here will be an object for sale that will survive the fact of exchange. Bliz-aard Ball Sale. A molded form prepared from (New York) snow, and so not an informal substance per se but one which nevertheless participates in the economy of anti-commodification essayed and prepared by the informal substances which emerged from play with bad areas.

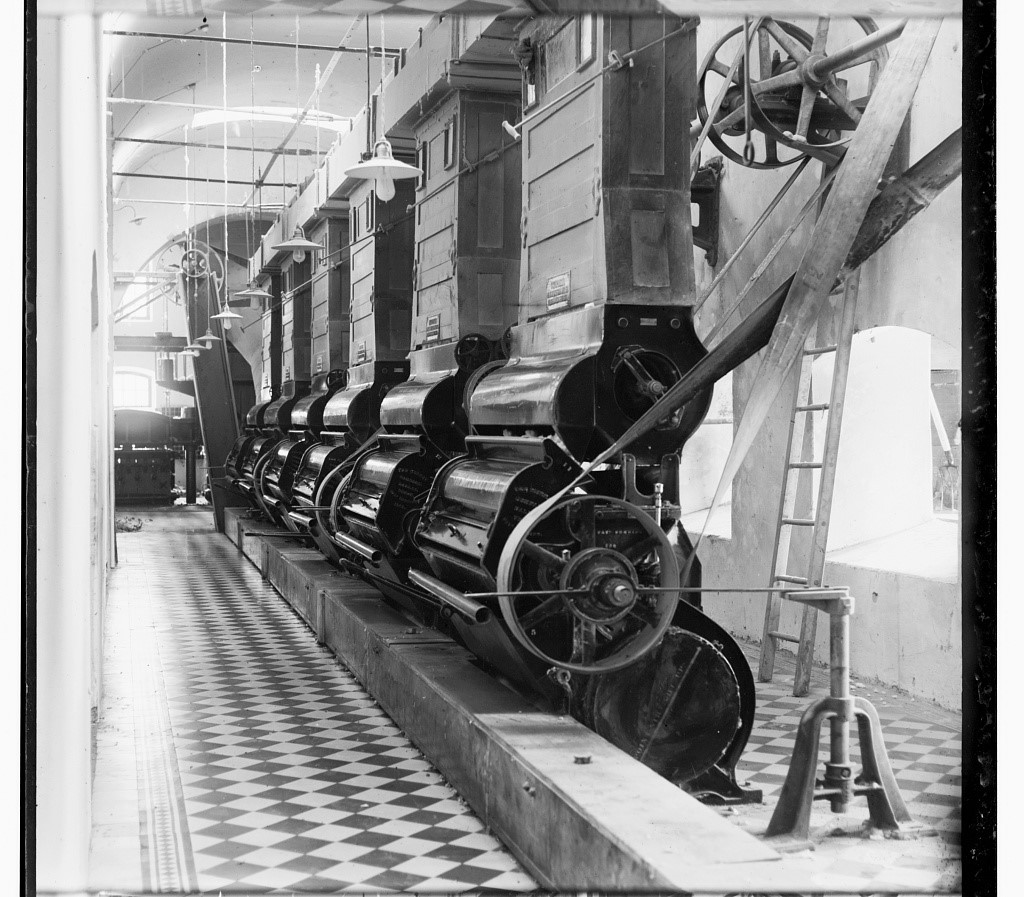

Bliz-aard Ball Sale permits another angle on work / labor production and, through a series of metonymic associations, the cotton gin, for we need to be reminded that the cotton gin, as conceived for the Americas by Eli Whitney, was meant to lessen the burden of labor, but instead vastly increased and expanded the burden of labor on enslaved Americans and in such a way that it became efficient to employ - which is also to say, to enslave - vastly more Black Americans. The cotton gin had exactly the opposite effect from what its creator intended and thereby increased suffering in the world. Allow me to put this another way, Eli Whitney’s cotton gin is one of the most stunning illustrations avant la lettre of the Jevons Paradox, that paradox first formulated by the nineteenth-century British engineer and mathematician William Jevons that for any technology made more efficient the end result will be an increase in overall consumption of whatever material it is that one first sought to conserve. Increased efficiency necessarily leads to increased consumption. Hammons’ refusal of the idolatry of labor - of demonstrable and demonstrative expenditure of energy as figured through “James Brown” - might thus be construed as a refusal that recognizes that labor is the violent insertion of the subject into industrial time. (It is, after all, John Dewey, not Heidegger or Ernst Jünger, who speaks of that condition in which work becomes labor.) Bliz-aard Ball Sale, on this construal, is not, however, merely a token of non-work but rather a presentation through metonymy of an economy of work-anti-work-non-work in a landscape - of which the rug is a synecdoche18 - for the production or work-like construction of something like cotton - the metonym par excellence of violent labor which, pace Du Bois on “The Black Worker,” could build a new world - namely, snow balls. Here is Jean Toomer’s sonnet, “November Cotton Flower,” from Cane, with the onset of winter,

And cotton, scarce as any southern snow,

Was vanishing.

With the onset of winter, cotton vanishes from the South, and its attendant or associative violence hibernates, as it were. What if cotton - and its attendant violences - could reappear in the North as snow - a violent rainstorm (blizz, dialectal), or a violent blow (blizzard) - something in its way as equally light as (Northern) cotton? Here they are, lined up on a rug / landscape arranged like cotton balls rhyming with snowballs. A miracle? That such a transposition might occur? Or that anyone - but not a Black person - could pay for snowballs in winter in New York (or anywhere else for that matter where snow customarily falls)? Cotton does not grow in winter, and Toomer’s sonnet, “November Cotton Flower,” imagines the immaculate appearance of such a November Cotton Flower as correlative of a possible time in which something new comes into the world, something that not even Superstition had seen before:

Brown eyes that loved without a trace of fear,19

Beauty so sudden for that time of year.

If cotton meant a new world, why might snow not also intimate (the equally spectral outlines of) a new world? A world not based upon labor, nor money and so where “all the realm shall be in common,”20 a world, it might be said, where the common is based upon talking, the encounter through speech? Hammons:

When you have an object between you and them, people will talk to you. They’ll say,

‘What is that? Is it for sale?’ But if you’re just standing on a street corner, everyone’s

an enemy of each other. But one object… it becomes a conduit for conversation with

with someone you’ve never met before.21

Du Bois on the coming of freedom to the enslaved at the end of the Civil War:

For the first time in their life, they could travel; they could see; they could change the

dead level of their labor; they could talk to friends and sit at sundown and in moonlight,

listening and imparting wonder-tales.22

- “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” King Henry VI, part 2, IV. ii. 73. One day whilst listening to the radio I decided that I had heard this line followed by knowing giggles once too often and that it was time that I knew what it meant in Shakespeare. I pulled down my copy and started to read and was absolutely stunned to realize that the sentence is embedded in a workers’ discourse on justice, labor, and social rank, a not unimportant part of which was the desire on the part of those who labored to eliminate money - “there shall be no money,” and “All the realm shall be in common,” an expression of the realm being held in common would be conveyed through garment: “I will apparel them all in one livery,” as sumptuary laws would be abolished. To this end, “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers,” presumably as lawyers are part of the machinery of policing social order. The argument does not end here and there is more than a whiff of Pol Potism involved - Shakespeare will, after all, compose Coriolanus - but the issues bearing upon the relations between labor, rank, and justice are all present where “Virtue is not regarded in handicraftsmen,” even though “there’s no better sign of a brave mind than a hard hand.” Whence the injunction, “Labor in thy vocation.” (King Henry VI, Part 2, IV. ii. 15.)

- Power and labor. Long before Marx, or Capitalists, for that matter, one of our oldest creation narratives, the Enuma Elish, and related Mesopotamian stories, made clear the cosmological significance of labor in the organization of societies. From tablet 1 of the Story of the Flood the problem is posed as follows:

When gods were man,

They did forced labor, they bore drudgery.

Great indeed was the drudgery of the gods,

The forced labor was heavy, the misery too much,23

and don’t you know, the gods complained. Throughout these narratives there are variations on a theme for how the (lesser) gods escaped the drudgery of labor, but perhaps the most powerful version is to be found in tablet 6 of the Enuma Elish where, after an intergenerational battle between the first and younger gods, Marduk, leader of the victorious younger gods, takes a defeated god, Quingu, on whom symbolic punishment will be inflicted:

They bound and held him before Ea,

They imposed the punishment on him and shed his blood.

From his blood he made mankind,

He imposed the burden of the gods and exempted the gods.

After Ea the wise had made mankind,

They imposed the burden of the gods on them!

That deed is beyond comprehension,

By the artifices of Marduk did Nudimmud create!24

That deed is beyond comprehension - no matter the translation, the effort is to convey what a miraculous thing it is to be able to create a being, a creation requiring powers great and exemplary even for a god, a being to bear drudgery and labor and, miracle of miracles, for that being, created by a god, to accept its condition. Here is Marduk’s speech, Marduk’s promise to his fellow gods - the 1% of their day -

“I shall create humankind,

They shall bear the gods’ burden that those may rest.”25

In other translations it is made clearer: So that the gods may be at leisure. The politics of labor is here the foundation of the politics of jouissance after which the architecture of society and sociality is wholly organized.

We have seen, says Postone, that Marx’s presentation indicates that general historical

emancipation is grounded not in the possible full realization of the already extant form

of production but, rather, in the possibility of its overcoming. This critique is rooted not

in what is but in what has become possible - but cannot become realized within the

existing structure of social life.30

My name is Bordeaux and Nantes and Liverpool and New York and San Francisco

not a corner of this world but carries my thumb-print

and my heel-mark on the backs of skyscrapers and my dirt

in the glitter of jewels!

Who can boast of more than I?

Virginia. Tennessee. Georgia. Alabama.

Aimé Césaire, Return to My Native Land, 1939 / 1956, translation 1968.

Endnotes

[1] William Shakespeare, King Henry VI, Part 2, ed. Andrew S. Cairncross (London: Methuen, 1957, 1969).

[2] See the website for My labor is my protest at White Cube, including the conversation between Theaster Gates and Tim Marlowe from which all my quotations from Gates are taken: https://whitecube.com/exhibitions/exhibition/theaster_gates_bermondsey_2012. Accessed 04-18-22

[3] On the cultural and class significance of the work of the hands, cf. Janet Zandy, Hands: Physical Labor, Class, and Cultural Work (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2004).

[4] Difficult not to hear father, also content, the father as content.

[5] Listening to Theaster speak, the poetic register is not merely in the (surprising?) diction - “when my dad is aging and things are decaying - spring is turning into the winter of his life” - but the very tender tone of voice.

[6] And this is so even in spite of the deeply felt valorization of folk art and song, of which the Negro Spirituals are very important examples along with the Blues, within the culture of Modernism.

[7] Jack Whitten: “LEARN TO HATE THE HISTORY OF ART AND ABOVE ALL DON’T TRUST IT.” Whitten, “Studio Log, 8 October ‘98,” Notes from the Woodshed (New York: Hauser and Wirth, 2018), 257.

[8] I have outlined a conception of abstraction in terms of veiling and masking in Michael Stone-Richards, “Underneathness - Surface - Work in McArthur Binion,” in McArthur Binion: DNA, ed. Diana Nawi (New York: DelMonico Books, 2021), 13-21, and in lectures during my time as Visiting Fellow in Critical Studies at Cranbrook Academy of Art, 2019-2020.

[9] See the low-res photographs of Tar works and the instruments of tar work (brush, truck, etc.) concluding with a portrait photograph of The Artist and his Father in My labor is my protest (London: White Cube, 2012), 25-35.

[10] See the Catalogue for Documenta 11_Platform 5: Exhibition (Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2002).

[11] David Hammons, in Kelly Jones, “Interview with David Hammons,” EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 249.

[12] Hammons, “Interview,” 249-250.

[13] Hammons, “Interview,” 249.

[14] Hammons, “Interview,” 249. My emphases.

[15] Hammons, “Interview,” 249.

[16] See Tom Finkelpearl’s conceptualization of this same material in terms of dirty materials, “On the Ideology of Dirt,” in David Hammons: Rousing the Rubble (Boston: ICA, New York: P.S. 1 Museum, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991), 61-89.

[17] On Lygia Clark, see Pierre Fédida, “Substance informe,” Par où commence le corps humaine: Retour sur la régression (Paris: PUF, 2000), 105-119, and Fédida, “Ne pas être en repos avec les mots: Entretien avec Pierre Fédida,” in Lygia Clark: De l’oeuvre à l'événement. Nous sommes tous le moule. A vous de donner le souffle, ed. Suely Rolnik and Corinne Diserens (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, 2005), 69-70.

[18] Robert Farris Thompson identifies the rug as a Moroccan rug and also observes, quite rightly, that the rug changed the situation. Cf. Robert Farris Thompson, “David Hammons: ‘Knowing their Past,’” Aesthetic of the Cool: Afro-Atlantic Art and Music (Pittsburgh and New York: Periscope Publishing, 2011), 100.

[19] My emphasis in order to mark what is immaculate in the sudden appearance of beauty.

[20] King Henry VI, part 2, IV. ii. 65.

[21] David Hammons, quoted in Filipovic, David Hammons: Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 73.

[22] W.E.B Du Bois, “The Coming of the Lord,” Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 (New York: The Free Press, 1992), 122.

[23] Story of the Flood, 1700 B.C.E., trans. Benjamin R. Foster, in From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia (Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, 1995), 52.

[24] Enuma Elish, 1900 - 1600 B.C.E., trans. Benjamin R. Foster, in From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia (Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, 1995), 39.

[25] Enuma Elish, 38.

[26] Cf. Robert L. Herbert, “City vs. Country: The Rural Image in French Painting from Millet to Gauguin,” From Millet to Léger: Essays in Social Art History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002), 23-48. In one way or another Herbert’s book of essays is concerned with labor and the technology of labor.

[27] Cf. Thomas Zander, Walker Evans: Labor Anonymous (D.A.P. / Koenig, 2016).

[28] I first chanced upon this photograph of Martin Luther King at Bowdoin in the exhibition catalogue, Le Modèle noir: De Gericault à Matisse (Paris: Musée d’Orsay / Flammarion, 2019), 21. In the context of Bowdoin’s 1964 exhibition, the image may be found online with further rich documentation at https://www.google.com/search?q=martin+luther+king+bowdoin&client=firefox-b-1-d&sxsrf=ALiCzsabmdW7UGy1 0zYcQURLgOYO0QqBJw:1661527092450&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwimyITh5uT5AhU-lWoFHUsBAacQ_\AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw =1152&bih=534&dpr=1.67#imgrc=JBlQMYUGEeLhzM.

[29] In another context, I shall touch on the life and work of Tillie Olsen as a way of exploring the way in which even, or may be especially, writers insistent on the social and political engagement of their practice still come up against aporias which lead them to recover the insights of the modernist fiction that sees the aesthetic as a refusal of labor and its political ordering - its ontology of commodification. See Michael Stone-Richards, “Aporias of Attention,” Care of the City (forthcoming, Sternberg Press).

[30] Moishe Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory (Cambridge: C.U.P., 2003), 360-361.

[31] Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination, 361.

It is our sorrow. Shall it melt? Ah, water

Would gush, flush, green these mountains and these valleys,

And we rebuild our cities, not dream of islands.

Auden, “Hearing of harvests rotting in the valleys”

I.

Care

Maggie Nelson. On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2021. 288 pp.

Emma Dowling. The Care Crisis. London: Verso, 2021. 250 pp.

The Care Collective. The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence. London: Verso, 2020. 114 pp.

The Politics of Care: From COVID-19 to Black Lives Matter. Ed. Deborah Chasman and Joshua Cohen. Boston: Boston Review, and London: Verso Books, 2020. 216 pp.

The Pirate Care Project. https://pirate.care/pages/concept/

Pirate Care is convened by Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak.

Pirate Care is a transnational research project and a network of activists, scholars and practitioners who stand against the criminalization of solidarity & for a common care infrastructure.

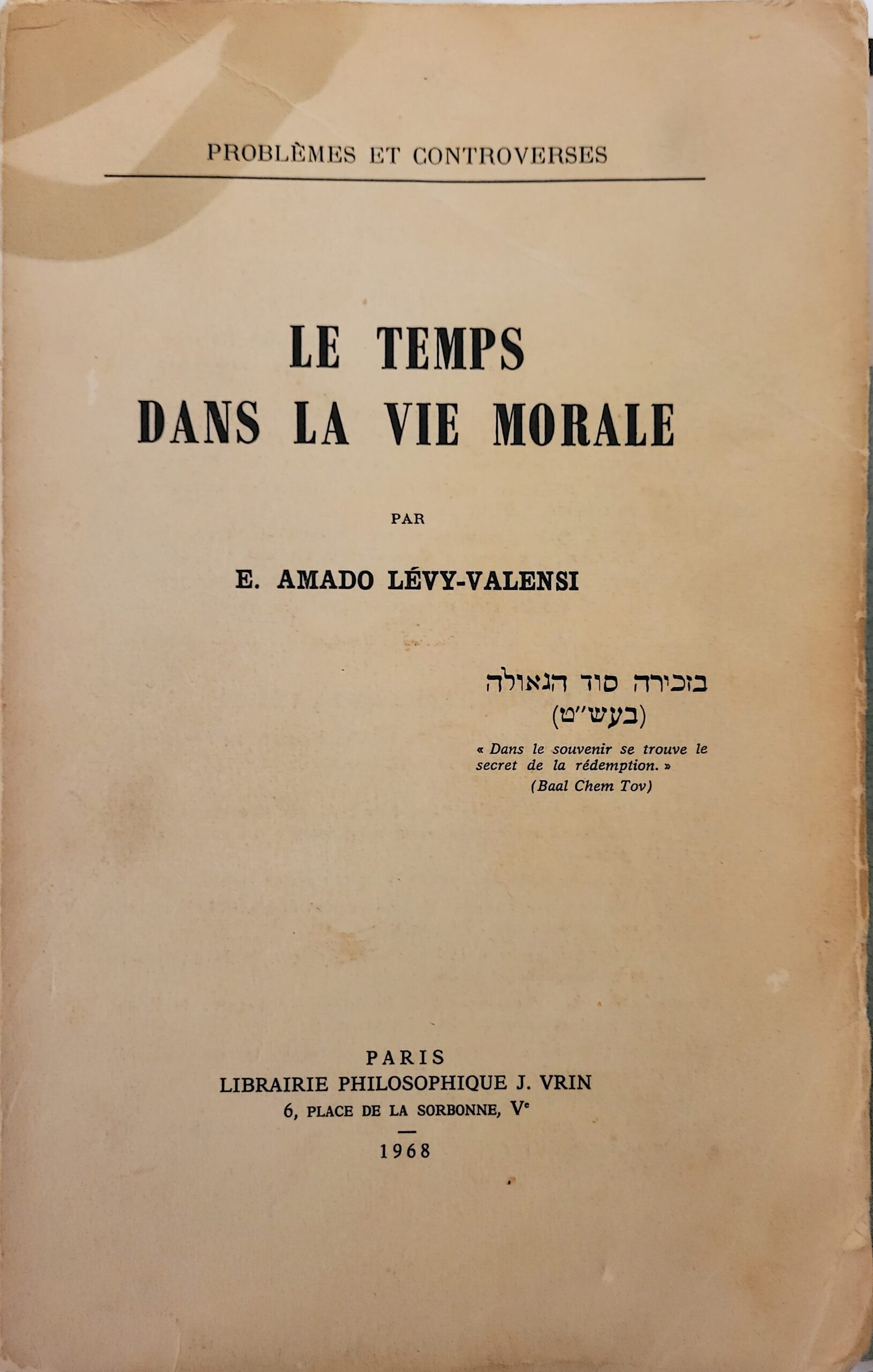

Care is everywhere, and everywhere marked by its absence. Hardly a week goes by without a friend sending me yet another reference to a new book or pamphlet on care. Since there is not only an ethic and politics of care but also, increasingly, an aesthetic of care, Maggie Nelson thinks it is worth challenging what is at stake in the new pervasive obsession with care, since who would think care a bad thing – but Maggie Nelson does not do warm and fuzzy, and in her own way she arrives at, but without channeling, Martin Heidegger (The Essence of Truth) and Orlando Patterson (Freedom, vol. 11) on the conflict inherent to any adequate conception of freedom and further, hence her title, On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint, that most of what is in play when people talk care is what Heideggerians would call ontic, rather than ontological. It would not be a distortion to say procedural, not of the nature of the being of Care in question, and thus peculiarly open to certain unacknowledged aporias of power, which is where a compelling collective such as the Pirate Care Project comes in for the almost brutal way in which it addresses the power dynamics in the business of caring, for there is no author or collective so direct, so stripped down in its demystification of care as a locus of state power and power differentials between individuals, no group which so seeks to strip the language of care of the sentimentality that seems to attach itself to care-talk as the Pirate Care Project at precisely the cultural and political moment when Care has broken through the obtuseness and distortions of reigning economic illusions worldwide and in the light of which Pirate Care proposes, well, a pirate form of Care as practice of solidarity: “Thus pirate care, seen in the light of these processes - choosing illegality or existing in the grey areas of the law in order to organize solidarity - takes on a double meaning: Care as Piracy and Piracy as Care.”2 Who – what – is or is not worthy of Care has, it seems, become the new demarcation between the human and the non-human even as it begins to enter social awareness that the human demonstrably is dependent on the non-human. Pirate Care may be guerrilla warfare from the non-violent souls of our dürftiger Zeit, our abject times.

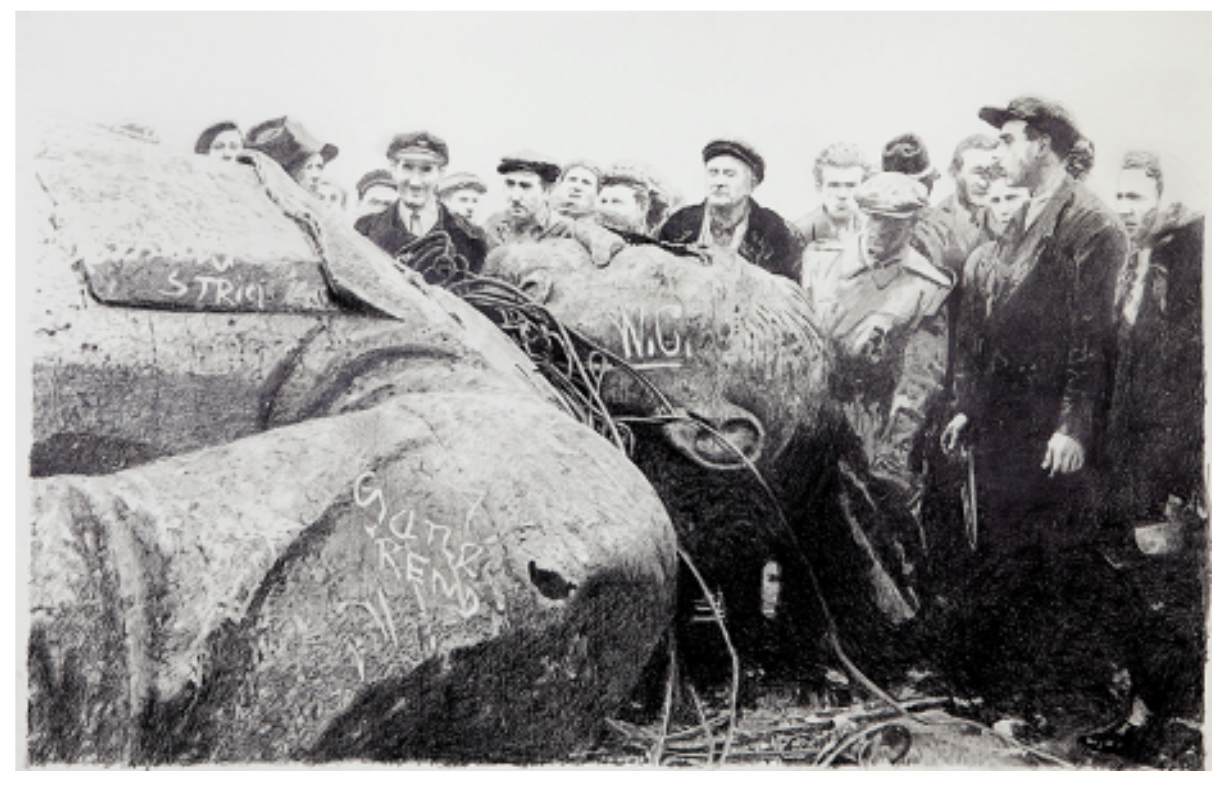

In March 2020, as American society began to accept that there was indeed something out there from which it was worth sheltering, I was, wouldn’t you know, teaching a class on Care of the City through an introduction to the feminist ethic of care tradition. It was straightforward to get students to grasp the significance of the gender and neglect of care practices, grosso modo, both receiving care and care-giving – of the body, the child, the house, environments, working with the routines which are the bases of larger habituations which establish spaces as livable or as sanctuaries, such care being the basis of images of relationships, and also (ultimately?) the City to which in certain moments of crisis we relate as a body in need of care, that is, presence, time, for which the work of the hands becomes a metonym. We even came to understand that we can care for strangers in a way which, say, and with all due respect to Senator Cory Booker’s Democratic Presidential Primary run, one cannot love whom or what we do not know. It was relatively easy, even, to grasp that gendered caring practices were, following Selma James and Sylvia Federici, a form of invisible work which erased itself as soon as it was accomplished3 thereby providing an image of why it was difficult to get society to accept that housework should be paid work (very few students would accept this proposal), that the unpaid care that went into the work of habits (housework) was the basis without which economies would collapse. What was more challenging, however, was moving away from voluntarist thinking – I choose to care; I do not choose to care because … - to a mode of thought where to care was not a choice, the position of Heidegger’s ontological conception of care, which is the basis for a mode of thinking of Care as response to the threat or fact of broken sociality, indeed, of broken sociality as an instance of retrait - retreat, withdrawal, voiding, collapsing, even dis-investment (in both the colloquial and analytic sense of this last term). Then came COVID-19 and the anxiety of what Heidegger characterizes as the collapse of familiarity, that is, the everyday, and the anxiety, that is, Care, induced by the confrontation with the loss of what is normally taken for granted. It is here that it is essential to be reminded of the Germanic etymology of the English care. The standard etymology of the English word care (from a current writer such as Anatoly Liberman all the way back to Skeats) points to “Anxiety, sorrow,” heedfulness, attention, even to lament, or to sorrow (“wholly unconnected with Latin cūra, with which it is often confounded,” say most dictionaries of etymology). So, the English care has built into its latencies and historical sedimentation the idea of grieving, or sorrowing for that for which one cares: the frail body of the loved one, the body about to depart for distant travels which induces melancholy and vague anxieties centered on the possibility of the non-return of the loved one, which may also be an image for, or a way of proleptically living the absence of. the body about to depart this world, the body incapacitated and thus utterly dependent upon the caring relation, that is, the relation of attentiveness, heedfulness, underwrit by a certain anxiety or anguish. Grief, however, collapses the grieving self and not necessarily because of what is already proximate to the one who grieves – and this is Heidegger’s insight into the non-voluntaristic dimension of Care, the ontology of Care, without which, the demand for care – also the demand for attention – is indistinguishable, and tellingly so, from a demand for love. …And so COVID becomes the home for the greatest drama of attending that we have all witnessed in our recent cultural memory, the murder of George Floyd, a graphic drama in the literal sense –- and here, I happened to be reflecting on a set of photographs on The Confederate Monument in the American South which my colleague Carlos Diaz had been developing for a book over a number of years, the opening of which, my response to seeing these photographs during COVID-19 and the murder of George Floyd, I reproduce here as it allowed me to think the relation between image and suffering, care and the collapse of familiarity, as well as image and mimetic desire in a framework where repression is the form under which things can be hidden – and disavowed – in plain sight.

II.

1. “The time is out of joint.” Hamlet, 1. v. 188.

When, just over a year ago, Carlos Diaz, the author of this collection of photographs, The Confederate Monument in the American South, came by my office in the College for Creative Studies in Detroit where we both teach and asked if I might be interested in writing an essay to accompany the work, I jumped at the opportunity not only to work with a photographer whose work I had come to admire but because I was very recently back from my first visit to Richmond, Virginia, which is also to say, I had been taken, as is every first-time visitor to Richmond, to Monument Avenue to see the collection of Confederate Monuments – and more thought needs to be devoted to this word collection and the phenomena which it evokes and shelters. I had never seen anything of the kind anywhere in my life! Parisians must be tired of the visitor’s response to La Tour Eiffel, just as many in New York are utterly unfazed by the Empire State Building – even after Jay Z and Alicia Keys’ “Empire State of Mind” – or many in Detroit are politely bored by the many visitors who are awed by the ruins of the Michigan Central Train Station, but during my stay in Richmond I do not recall anything blasé in anyone’s conversation about the statuary on Monument Avenue and this was not surprising for the city that had once been the capital of the Confederacy is now a bastion of liberal and progressive wealth and privilege, and just as no one could ignore the monuments no talk could not be also simultaneously about the question of the monuments: the entangled politics of their afterlife, the complex ethics of aggression and impotence entailed in their cast shadows, and their continued injury to thought. If, after the collapse of Communism and the Warsaw Pact as symbolized by the Berlin Wall, the world had become accustomed to the idea that with the collapse of a governing order goes also the monuments to its own magnificence – something repeated and televised the world over with the collapse of the regime of Saddam Hussein – then it must seem all the more jarring and discomfiting to encounter the phenomenon of the Confederate Monument in the American South: Everywhere else in the modern and contemporary world the monuments of losing regimes in Budapest, Hungry (1956), in Accra, Ghana (1966), in Tehran, Iran (1979), in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1991) – and no regime loses because it is good or virtuous – are by popular assent pulled down, dragged off, and melted or broken down or, as with the recent pulling down of the statue of the British slave trader Edward Colston in the English port city of Bristol, thrown into rivers or oceans - or occasionally put into museums as apotropaic objects: Look on this and shudder!4 It is not easy, after all, to imagine a German person saying, Yes, let’s keep 750 monuments and commemorative objects to Hitlerism because that is after all part of our history and heritage and you can’t erase history!

2. “Be you my time,” Troilus and Cressida, I. iii. 313.